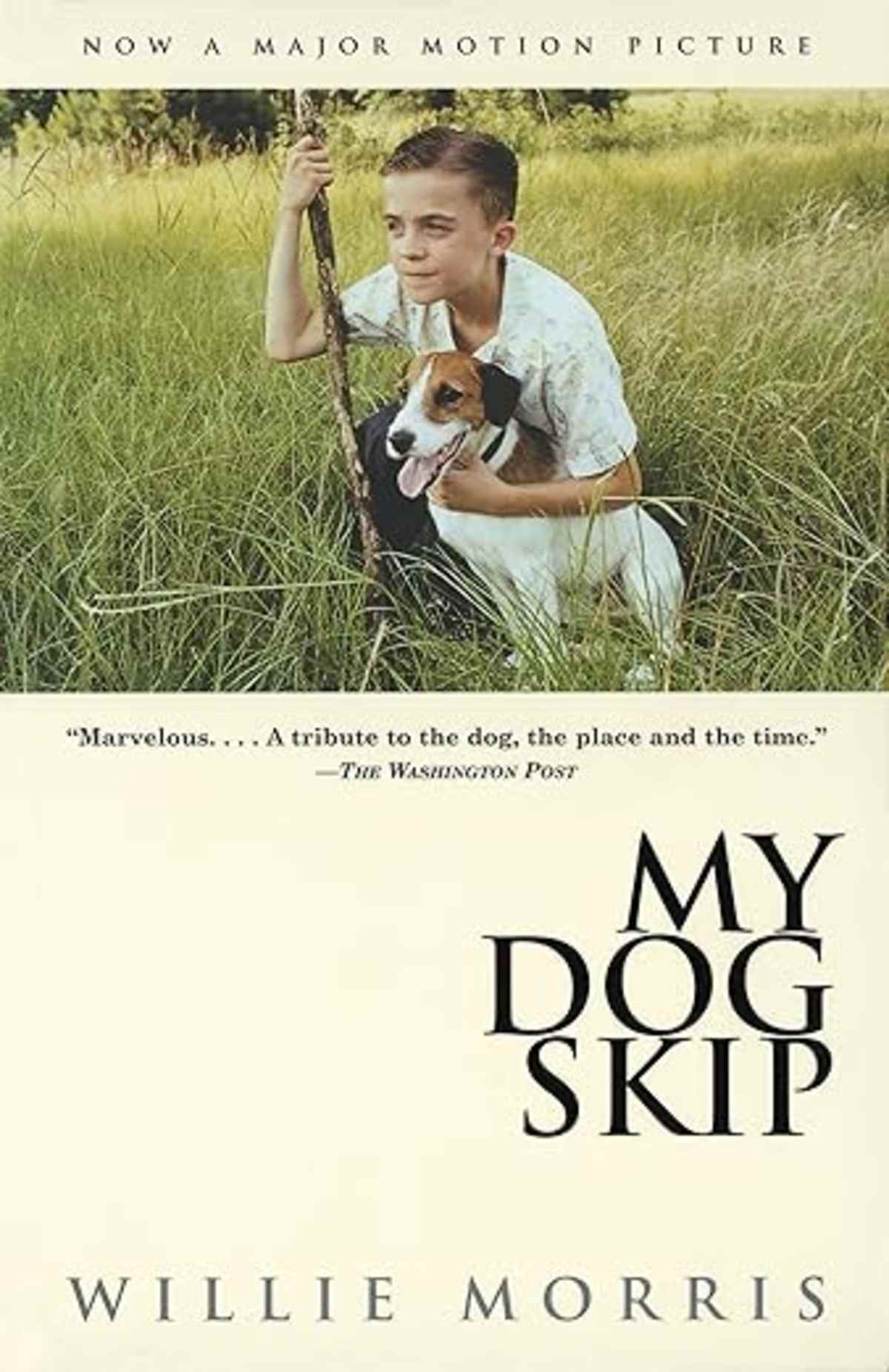

My Dog Skip (1995) by Willie Morris (1934 – 1999)

(This passage was probably from 1948.)

Autumn: Our region of America never had the great flamboyant, bursting beauty of northern autumns, but there was a languor to our Octobers and Novembers, especially in the dry falls when the foliage was so profound and varied, and the very landscape itself would be imbued with a golden, poignant sheen.

One Saturday during the autumn I woke up quite early to take full advantage of the fresh, free Saturday ambiance, and in such a disposition I woke up Skip rather than the reverse, and we lounged around in bed for a few more minutes as I considered the days unique possibilities.

My room was quite small but nonetheless contained an unusual number of interesting items: colorful pennants from a dozen colleges; the German helmet and belt hanging from nails on the wall; horns from a dead cow; a photograph of the 1946 St. Louis Cardinals; my father's old baseball glove; a bookcase with books by Mark Twain, Zane Grey, Dickens, and Poe; the rattlers from the rattlesnake I had killed in the woods; four chunks of petrified mud picked up along ancient creekbeds; and various photographs of Skip with Rivers Applewhite, the other boys, the bulldog Buck with whom he had shared the first prize in the dog contest, and myself.

Lying there in bed with Skip beside me, I gingerly recalled the major events of the day before. After school Friday he had been waiting for me at his appointed place on the boulevard. We immediately went home and got my bicycle and rushed out to the black high school football field to see the Black Panthers play a game and to imbibe the lavish flair of their players and fans. They played in the discarded uniforms of our high school, so that their school colors were the same as ours, and they even played the same towns up in the Delta that our high school did. Skip and I normally sat on the sidelines next to the cheering section, but one afternoon the referee asked me to carry one of the first-down markers, and Skip followed closely beside me during that entire game as I fulfilled these official responsibilities. Next I conjured the scenes from last night's white high school game, which Skip, Peewee, and I had watched from the end-zone bleachers, and the infectious undercurrent of excitement there, for on Fridays in the fall you could almost feel this tension in the atmosphere, the unreserved reverence for the game itself, the awesome thuds of big old boys running headlong into each other, the off-key marching bands, the cheerleaders making pyramids of flesh, while all through this pandemonium the spectators slapped at the manifold Delta bugs attracted from the nearby swamp-bottoms by the lights of the stadium.

At about nine o'clock I got dressed in a pair of blue jeans, tennis shoes, a white T-shirt, and a green baseball cap with a Y on it. Skip and I ate some raisin bran in the kitchen; then I led him outside for a lengthy session of retrieving sticks. It was Indian summer and everything—the earth and the trees, touched by the airy sunshine—was the lazy golden-brown of that sad and lovely time; there was the faint presence of smoke everywhere, and the smell of leaves burning, and sounds and their echoes carried a long, long way. Wherever you looked there was a truckload of raw cotton coming in for ginning; along the country roads and even the paved avenues in town you could see the white cotton bolls that had fallen to the ground. The county fair was on, and every night that week we had taken in the 4-H exhibits—the vegetables, and the bottled preserves of all the shades of the rainbow, and the pumpkins, and the great slabs of meat. How Skip loved those county fairs¡ He strolled the grounds with the other boys and me in a spirit of fine titillation, ate the cotton candy Rivers Applewhite gave him, and waited impatiently while we took the carnival rides. I had tried to get the man who ran the Ferris wheel to let him go on it with us, but he was not sympathetic. “This contraption ain't no place for a dog.”

In our backyard on this Saturday morning, Skip was by now a little tired out from his exertions, and it was time to consult with Henjie. I went into the house and told the telephone operator his number (it was 27; mine was 243; my father's office was 1). When Henjie answered the phone, I wanted to know if everyone was coming to the football field, and he said they would all be there at ten; we had stopped going to the Saturday Kiddie Matinee when the war ended and we felt we had outgrown it anyway. I fiddled around with the radio awhile, and read the Memphis Commercial Appeal for the football scores; then I got on my bicycle and headed up the street toward the football stadium, with Skip following, stopping every so often for him to examine a dead frog or some other lifeless object or to greet an old lady.

When he and I reached the field, the same site at which he had earlier set the world record for fox terriers, we ran a few wind sprints, then examined the cleat marks that had been made in the turf the night before by our high school heroes. Three thousand people had been in these grandstands and the bleachers just a few hours ago¡ I did a pantomime of a forty-three-yard scoring play, dodging Skip and the imagined tacklers on last nights exact route to glory. Then the boys showed up, including Peewee with his official Southeastern Conference football with the dangling lace for Skip to carry in his mouth on his running plays, and we chose up sides and played a brisk brand of tackle until the twelve o'clock whistle blew at the sawmill. The only injuries on this day were to Peewee's big toe, which he claimed he sprained when tripping on a cleat mark, and to Henjie's head, which he said Big Boy had mistaken for the football. The final score was 86-69, my team over Muttonhead's.

The afternoon held many possibilities, but this one began with fried chicken and biscuits and other delicacies at Bubba's house, for his mothers refrigerator contained a plethora of riches mournfully absent from the one at my house, and then an interlude listening to the Ole Miss or State football game on the radio, because there has always been a religiosity to college football in our region, and Saturday is the holy day. After that we rode our bicycles to Main Street to see the latest Boston Blackie movie, then returned to my house to get our DeSoto and take a spin around town, from the telegraph shack at the end of Main Street to the Country Club at the rim of the Delta. Only a scant minority of its citizens had never seen Skip behind the steering wheel, but we managed to locate a little store on Brickyard Hill which was virgin territory, and the inevitable old man shouted: “Look at that ol'dog drivin'a car!”

Then we proceeded to Henjie's house to listen to the college football results on the radio. We lounged on his front porch and watched the leaves drift from the oak trees and listened indolently to the scores—first those of the little schools in the East like Williams and Colby and Amherst and Niagara, or Allegheny and Susquehanna and King's Point and Lafayette; then the Ivy League scores, which were just exercises; on to the big midwestern and southern ones that really mattered—moving slowly across the country like a great roll call of America.

After that Skip and I took off for home, walking down the hills toward the quiet flat streets, and making it just in time for hamburgers and french fries. After supper I turned on the lamp in the front yard and put the portable radio on the porch, tuning it to the LSU game from Tiger Stadium in Baton Rouge, and Skip and I played football again by ourselves, I making up the whole game to the accompanying din of the thousands from the radio, racing ninety-five yards for fictitious touchdowns before seventy-five thousand cheering fanatics, intercepting enemy passes in the dying seconds of the fourth quarter, kicking forty-six-yard field goals against thirty-mile-an-hour winds. By now it had been a long autumn Saturday. Old Skip and I stretched out on the cool, wet grass. I used the football for a pillow and he lay down beside me and we gazed up at the stars until it was time to go in to bed.

In remembering moments such as these, I retain the sad-sweet reflection of being an only child and having a loyal and loving dog, for in the struggles of life, of the dangers, toils, and snares of my childhood hymns, loyalty and love are the best things of all, and the most lasting, and that is what Old Skip taught me that I carry with me now.